Richie George

This Hoe Got Roaches in Her Crib

By Quan Millz

Quan Millz Books. 376 pp. $13.99

Late on a Tuesday night, I scrolled through my TikTok feed. A video of a middle-aged Black man in an old sedan appeared. He was screaming, “Hey guys, it’s international best-selling author Quan Millz here!” The pen name immediately caught my attention. I scanned his storefront on TikTok Shop, primarily vending tomes from Millz’s own eponymous distributor, Quan Millz Books. Popular titles include Old Thot Next Door, Pastors Eat Pwussy Too, and Pregnant by My Granddaddy’s Boyfriend. But his most acclaimed novel—if the comments section is any indication—is This Hoe Got Roaches in Her Crib.

There are those TikTok influencers who host live readings of his work to garner engagement through commentary. There are the others who argue for his place in the English literary canon alongside Shakespeare and Milton. The significance of Millz’s work—seemingly infinite with more salacious titles surely to come—is inseparable from the popular demand for gripping and comedic depictions of Black urban life. And Quan Millz supplies them in plenty. Through absurd titles, obscene, AI-generated covers, and sexually charged language, Millz stokes the sense of scandal and spectacle that typifies his books and bolsters their commercial success.

Unsurprisingly, he has yet to receive a sustained critical response. Besides limited coverage in WIRED and NPR, Millz has been disavowed by Black literary scholars such as Jacinta Saffold, who said in a 2023 interview that Millz fails to provide “genuine commentary on the Black experience.” But the dismissal of these novels as either controversial or tasteless thwarts an honest encounter with a pressing question: Why has this kind of urban fiction attained such unusual prominence in recent years? If depictions of life in the inner city are only valued by the culture industry as gratuitous forms of popular entertainment, what does that say about the value of Black life in America more broadly? And can we find, anywhere in Millz’s novels, anything beyond the morbid interest that has so far defined them?

***

Fredquisha Pierce is the titular “hoe” in Millz’s This Hoe Got Roaches in Her Crib. She is the archetype of the Black “welfare queen:” a ghetto Medea who neglects her children as a way to take revenge on her incarcerated ex-boyfriend, Austin Watkins. Always adorned with a “sour-smelling bonnet,” Fredquisha is a morbidly obese woman constantly in search of men and drugs. With a kind of magical realism, roaches emerge from her flesh when she eats junk food from the local deli. As a result of casual sexual encounters with her local dealer and others, she suffers from STIs, yeast infections, and a “turbulent case of bacterial vaginosis.” She beautifies herself with cosmetic surgery to please her partners, boasting “double-d [sic] cup dropping titties” and a butt that looks like “two steroid-injected brown potatoes lumped together.” The sex she has always ends up being violent, even when it starts consensually, and the resulting damage is left unaddressed because Fredquisha lacks access to healthcare. She barely manages to hold on to her Section 8 apartment, and subsists on monthly checks from the government.

Fredquisha is staged against her eternal rival: Austin, her baby daddy, who, like other Black baby daddies, is in prison. After serving an unspecified amount of time in Chicago’s Cook County Jail, Austin is determined to regain custody of his daughter Myyah from Fredquisha and return to the outside world.

The novel is principally concerned with Myyah’s worldview. Growing up with an absent father, like many inner-city Black girls, Myyah appears intelligible only as the product of vexed attachments. She is, simultaneously, the exposed wound of accidental intercourse, the abused offspring of a disaffected mother, and the estranged relation who gives Austin a sense of purpose following his release from prison. Her existence dramatizes the popular narrative of the Black family. With a welfare queen for a mother and a violent criminal for a father, Myyah is the daughter of two tropes, yet she herself remains without her own account, her own bildungsroman. She is the problem at the heart of the story, rather than its willing participant. As a symbol, she is the evidence of distressed Black kinship, the fatal outcome of poverty and government neglect.

Revolving around this insurgent triad is a constellation of men and women who feel they have a stake in Myyah’s future. Cops, guards, psychiatrists, social workers, and other drones of the state regulate her passage from one family member to another and evaluate competing claims on her custody, including those of both her grandmothers. Ultimately, Myyah dies a tragic death, the proximate cause of which is state-subsidized housing—namely her mother’s Section 8 apartment—which exposes her to bacterial-encephalitis-infected roaches only days before her grandmother could legally claim full custody. In Millz’s inner city, characters are trapped in a vicious cycle of familial estrangement and loss, directly enabled by a failing welfare system. The Black Ghetto, as the novel’s setting, is thus a kind of stock exchange, and the Black female body its currency of choice.

The roaches’ ubiquity in the book seems to be about how it feels to live within that system. They literally creep into the narrative, starting with the 1,861 that infiltrate Fredquisha’s home early in the story—a conservative estimate that Millz later revises, claiming that a “roach galaxy” may in fact lay behind Fredquisha’s stove and fridge, living off pizza, fried chicken, or whatever else she had that evening.

Millz analogizes the roaches and his Black characters, because they both constitute a “surplus population” whose lack of value is linked to their social position. Like Fredquisha, the roach is characterized by its exile to dark corners, or ghettos, where roach families, like Black families, subsist on the surpluses of production. For roaches, it is the Black urban family’s diet of junk food. For the Black urban family, it is the government checks funded by American taxpayers. The conditions this excess can buy, however, do not protect their beneficiaries from violence and death. When roaches search for more food, Fredquisha kills them. When Black urban residents occupy disinvested cities, they are exposed to police violence, food deserts, and ill-equipped hospitals. The roaches in this book host “homegoings:” funerals where they grieve for life not understood as grievable by their Black overseers, in a way mirroring how American society at large undervalues Black life. The Black Ghetto is Black life’s most troubled corridor, where fatal dramas play out repeatedly, to reify received ideas of Blackness in the popular imagination.

***

Reading Quan Millz’s work is unsettling. Nevertheless, sustained engagement with This Hoe invites us to consider the millions living in America’s inner cities, whose lives have been caricaturized and repackaged for popular consumption. For many, it feels impossible to move past the novel’s salacious cover, to care for the story and its characters, even as they are thrust into a tragedy without end. But the book raises what I believe to be the question of Black representation in popular fiction: what is the difference between the value of Black life and that of its depictions? Is there a difference at all?

Millz’s next book will surely offer yet another view of the ghetto’s terror and its attendant comedies. In particular, it seems sexual violence against Black bodies will only continue, as will the parade of stereotypes about Black people. These tropes tend to ossify in readers’ imaginaries, like an eternal minstrel show played out for their enjoyment. The conclusion? There is no “outside” beyond the ghetto for Millz’s Black characters, or for the real people they represent.

Still, one wonders whether these books lend themselves to a deeper reading, even as they appear to play into old narratives of Black inner-city life. This Hoe is particularly concerned with the history of Englewood, a Chicago neighborhood that is the novel’s main setting:

Englewood wasn’t even one of the biggest neighborhoods in the city—it was a section only three square miles on Chicago’s mid-South Side. Yet hyper-poverty, extreme gang violence, drugs, prostitution, murder, domestic abuse and other ills that typically plagued inner cities defined life for residents in the area. Frequent streams of gunshots, sobbing mothers, crackhead fights and roaring bass heavy trap music was the soundtrack to life.

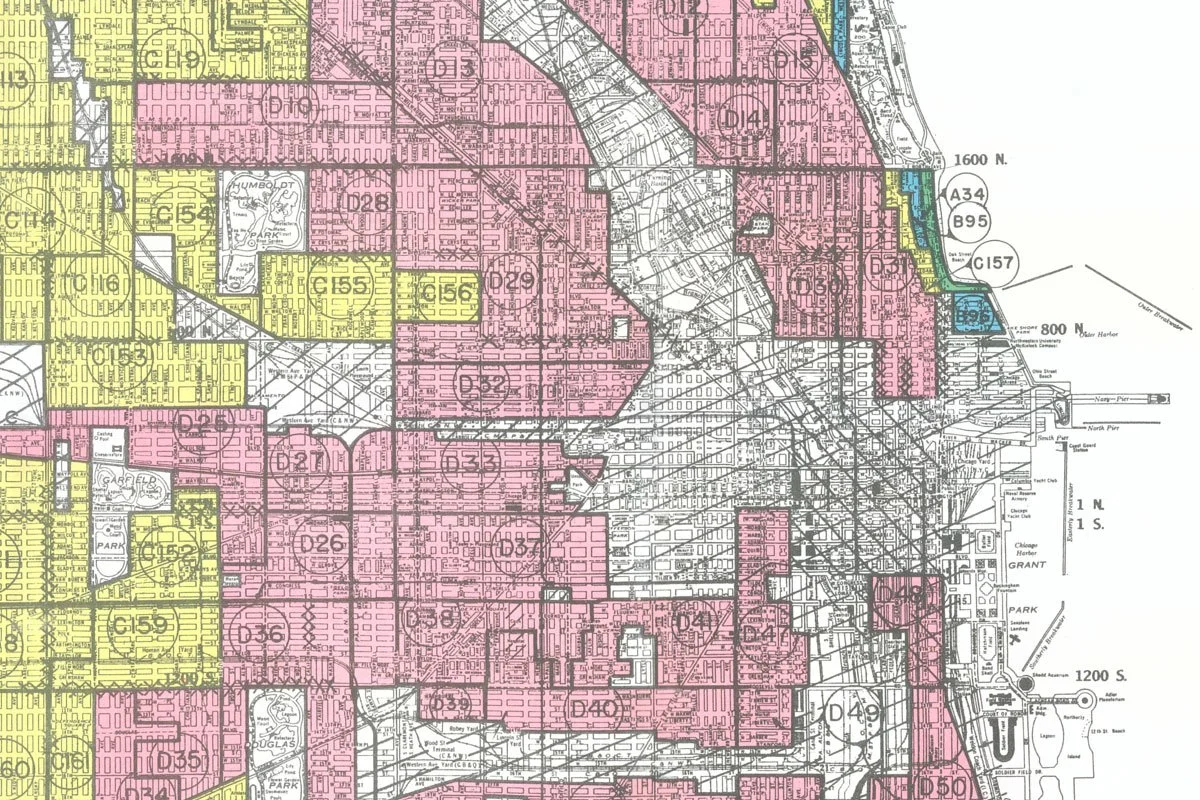

Englewood has all the typical markers of Black ghettos, and yet is more than a static site of trauma. It demonstrates, in its structure, a vexed history of social transformation. Millz narrates the town’s transition from a “once-prosperous” community of “middle-class Black families” to a “living nightmare of urban desolation and decay.” The future of Englewood could have been a future of Black life, liberty, and prosperity, but, “like many other Black neighborhoods,” its Blackness condemned it to what prison scholar Ruth Wilson Gilmore calls “organized abandonment,” a mid-twentieth-century phenomenon describing how the state left communities behind through disinvestment and privatization. “Truth be told, the entire neighborhood needed a big red X on it,” Millz’s narrator remarks.

But it would be facile to view Englewood only as the scene of organized abandonment and its afterlives. The inner city and its residents continue to ache beyond and after the site of historical injury. In This Hoe, Ms. Watkins, Myyah’s paternal grandmother, is the owner of “a big, six-bedroom McMansion” in a gated suburban neighborhood, yet she is perpetually caught up in the ghetto due to her family’s troubles. As she drives into red-lined Englewood after a night of babysitting Myyah, she is almost injured in a car accident, and later she must mourn her granddaughter’s tragic death. All Black people, whether they live in the ghetto or not, are thrown into a relation with it, and through it, the precarity of Black life.

Millz unfortunately reproduces ridiculous stereotypes about Black city dwellers because of the simple dynamics of the popular fiction market: for his books to sell, they must continue to grab people’s attention, and one way to do this is through scandal and outrage. However, a counter-reading of his work might allow us to transcend the limitations set by commercial pressures. We can uncover, beneath the spectacle, an account of Black urban life that reckons with its historical exclusion and appreciates those who live inside the wreckage. By using urban fiction not merely as a source of cheap entertainment—but as a genuine window into the realities of the ghetto—we may begin to understand how and why Black life and Black culture remain parochial in the American imagination.

Such an encounter admittedly requires a departure from Millz. His novels are too immersed in generic, overburdened depictions of Black urban residents, which drowns out the more lively tenor of Black social life. Nevertheless, Millz’s brief moments of genuine insight, including his descriptions of Englewood, bring readers into contact with the living conditions of the Black ghetto, allowing us to see them as historically contingent products of both personal choice and structural problems. Englewood’s tragedy, which is the tragedy of inner-city neighborhoods across the country, diagnoses the state’s role in sustaining a cruel maldistribution (to reference Deleuze) of money, capital, labor, and the essentials of life itself, at the expense of Black people and Black culture.

***

Do Quan Millz’s books offer any solution to this crisis beyond their adoption of its aesthetics? The books offer only a tenuous answer, which is often left out of their critical and commercial reception. There is no Armageddon of social change for Myyah, Fredquisha, and Austin. Millz instead suggests that a simple moral code could outweigh the force of America’s racial terror:

A lesson anyone, regardless of race, socioeconomic status, gender, culture, sexual orientation, etc., should learn. Love thy neighbor…And so, for Austin’s forgiveness of everything that transpired and his desire to move forward, for Austin’s pulsing desire to see beyond everyone’s flaws as so many people saw beyond his, he did his best to make sure everyone had a chance to get things right before it was too late. Too late before another girl, or even boy ended up like Myyah. She was an example, and all we need is one sacrificing example to know we should learn to love one another.

After Myyah’s death, Austin is invigorated with a joie de vivre that compels him to fight for the improvement of Englewood. He starts a real estate business and a nonprofit organization to support the city’s “troubled youth.” He helps his partner found a low-income clinic, and, thanks to his rediscovery of “forgiveness,” houses Fredquisha’s mother after her passing. Austin becomes an upstanding hero whose economic success and familial unity foreshadows Englewood’s return to its long-lost prosperity. Millz deploys the Christian principle of loving thy neighbor to suggest that love among community members can overturn the social disparities of the inner city.

How radical is this project? Not very. It’s a refurbished Christian ethic. Myyah is Jesus, and her sacrifice motivates Austin’s program of race uplift—a conclusion that can easily come across as artificial consolation. But the ending may also have something to teach us: that there is value in holding radical optimism for Black life. If we let the ghetto run wild with possibility, if everyone indeed had “the chance to get things right,” then what a great world that would be for Black people.

We have yet to build a world that realizes the hope of emancipation or exceeds the terms of flat Black representation. But in the meantime, let us read beyond those limits, and imagine a form of social life that bursts forth from the darkness of Millz’s ghettos. To make good on our wildest optimism for the future of Black life, we must fight for a world where imagination becomes reality: the yet unexpressed “outside” of the minstrel show in which the characters of urban fiction live.

Richie George is rooting for everybody Black.